In Tamil Nadu, the bizarre green village of Ati Malapattu, 14 km from Arani, wakes up before sunrise. Until dawn, the roads are alive with color: long rows of silk threads are carefully spread from the end to the end, beating it gently to bring out its brightness. Children run around, carry ropes, sticks and scissors, help their weavers-mother-father with this centuries-old step, known as street warming, after which threads find their way for loom, ready to be woven into a silk saree.

Learning from heritage artisans should be one

“Why is this process done before sunrise?” Someone asked, got upset.

The question cut through a weavers’ stable fabric rhythm. The doubts about his centuries -old family crafts were unusual. He said, “After sunrise, the heat will break the silk thread, and they will not be tensile and tight, which will be drawn as sarees,” he said, looking up. He was a student of Swathini Ramesh, National Institute of Fashion Technology (NIFT), Chennai. She quickly gave her reply in her notebook as she was curiously watching.

After completing their second year of graduation in the design (textile design), Swathini and her 19 classmates came to the Ethnimalapattu for a week to know about their silk saree production as part of their craft research and documentation component, as determined by central textiles.

“As part of his course, students from all NIFT centers including Chennai visit crafts groups like Arani who specialize in traditional crafts. This helps them develop respect for centuries old arts of India,” said Professor Divia Satyan, Director, Director, NIFT Chennai.

They are living, work with artisans, documentation of craft and present it as a report. “It helps to preserve and document heritage arts and crafts. Then, it gives students the idea of taking these traditional crafts to a new level. Then, in the final year, in the final year, they return to the cluster for a collaborative project and apply the intervention – such as how to use resources without affecting the environment,” Associate Professor G. Krishnarj, Textal Gainez, Text Field Department said.

Class lesson to life

“This was a chance to see the principle of our classes alive in threads and loom,” Arushi Bansal said, another student who visited Arani with Swathini. Although there was a loom in his classroom, he was left strange after seeing a full -sized handloom in Arani. “We weave a cotton cloth in the shape of a handkerchief in college. But it was not a real deal,” said Swathini.

“Arani was older and was in a pit,” said Arushi. A pit handloom is a traditional loom with a wooden frame, and is used to weave silk or cotton. The weaver sits on a shallow pit in the floor. Paddles in the pit control the up-end-down movement of the taunt threads (long vertical threads), while the weaver’s hands pass through the shuttle carrying the horizontal threads through them. By repeating this rhythm for hours, threads slowly turn into clothes.

“I laughed when one of the students asked why Loom sits in a pit instead of land. I explained that it allows me to work for hours without breaks. Sitting above the pit with my feet makes it easy to operate the paddle, while my hands are free to pass the shuttle and manage the threads,” Venkson e, a 37 -year -old. This loom helped in his seat. “I don’t want to bend at the yarn and I need to hurt my back.”

Arushi said that he learned more during the week with Arani weavers in a two -year class study. “These weavers come only by practice in hand by hand. If they have to make an infection in another color in a sari, the weavers manually bitten about 4,000 distorted threads manually, they take the other color and knot it with 4,000 loops before weaving. A saree in a handloom.

Professor Krishnaraj said that saree design cannot be carelessly done. “The students observed the taxes of various sizes and abilities. When they could understand that only a few taxes allow two-inch-live design, while others give designs with a length of four inches. There is no design that corresponds to one-size-fit-all.”

Students also visited mulberry gardens and cereal areas from where silk is generated from silk pests.

Seeing their learning center again

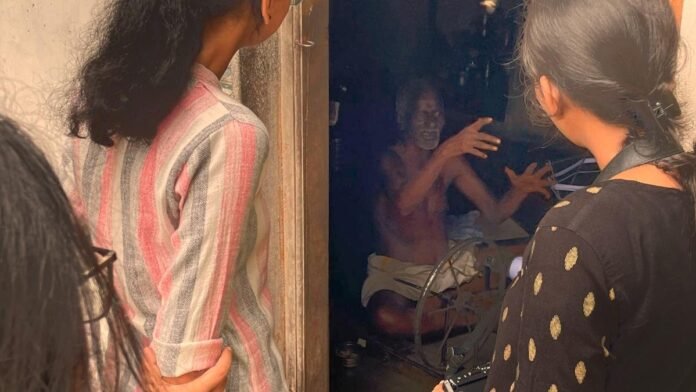

Swathini said that Arani weavers are very hospitable people. “They gave us food, placed flowers on our head and even adjusted non-tamil-movable students in our batch. He taught me weaving in his handlooms.”

During the seventh semester, students are asked to return to the cluster to work on a project. “I wanted to use natural and plant-based dyes to create a bridal wear brand with my silk. They agreed to send me silk so that I could dye it with natural colors. They also placed a section for natural-dai silk sarees for sale in their cooperative society showrooms.” “They encouraged me that it is important to promote natural colors as it is less dangerous for the environment.”

After college, Swathini started a brand and is an outlet in Thiruvarvarduu, Chennai and sells silk from Arani to silk sources, among various places in Tamil Nadu.

Despite being one hour away from Kanchipuram, Arani silk is different. “Kanchipuram Silk is a very heavy and traditional material. But Arani silk is more contemporary with modern motifs, which are mostly used for office and casual wear. Arani is also famous for check (design). It is also low of saris,” Svathini said.

On the other hand, Arushi is planning to cooperate with weavers to promote and popularize its production with social media and branding. “He gave a lot of love and care to a non-tamil speaker like me. They did not even speak English, but I could understand what they were communicating with some sign language and weaving practices. He opened his homes, loops and craft secrets for us.”

Venkatsson said, “The younger generation is slowly getting away from our family and generation -long art. We want more weavers to join us. Our cooperative society also provides handloom training even with a small stipend,” said Venkatsson.

Published – 04 September, 2025 05:23 pm IST