Un Certain Regard is like the poor cousin at the Cannes Film Festival that is often ignored and treated like a doormat. We know the story of Cinderella, right? But like the poor girl in the fairy tale, Un Certain Regard, a class that is often playing second fiddle to the competition has this unique ability to emerge from the sidelines and shine. (Also read: Drama seen outside theaters at Cannes Film Festival)

In a recent interview, the festival’s big man, Thierry Frémaux, said, “The purpose of Un Certain Regard was to expose new trends in cinema, new paths, new countries. It is a selection that supports young filmmakers, especially female directors, and prepares for the emergence of future generations. We look for style, originality, narrative power and conviction.

Peter Bradshaw, chief film critic of The Guardian, said, “Un Certain Regard was a game changer when it was founded in 1978 by Gilles Jacob, Frémaux’s predecessor. This basically doubled the size of the official festival. There’s twenty extra titles in a very important sidebar – it’s taken very seriously – and with that sidebar it’s created a huge challenge for other festivals, because, you know, other festivals that maybe have those titles. Wanted, they feel they are being harassed in an unrequited relationship.”

These films are the future of cinema. They are harbingers of things to come. In recent times, many directors who have cemented their place among the competing titles have started their Cannes journey from the streets of Un Certain Regard, which translates as A Certain Look. These men and women took their baby steps into the realm of this category, which – away from the hustle, bustle, push and pull of everyone’s favorite and much-awaited competition – provides a wonderful opportunity for reflection and ultimately glory.

Ten years before South Korean writer Bong Joon-ho won the top prize, the Palme d’Or, he surprised almost everyone with His Mother, a tender tale of a mother-son relationship that borders on possessiveness. Is.

Sweden’s Ruben Östlund, who won Palms for The Square (2017) and Triangle of Sadness (2022), was awarded the Un Certain Regard Jury Prize in 2014 for Force Majeure.

Another excellent example is the 35-year-old French Canadian writer Xavier Dolan, who is this year’s president of the Un Certain Regard jury. Two of his works, Heartbeats (2010) – written when Dolan was 21 – and Lawrence Anyways (2012), were featured in Un Certain Regard. Her next two films Mommy (2014) and It’s Only the End of the World (2016) won top competition awards.

“I believe what young filmmakers are putting forward this year is very exciting, you will see,” Frémaux said – perhaps with a sense of pride.

In fact, Un Certain Regard has evolved over the years into a wonderful launchpad from which poor Cinderella transforms from an ugly duckling to a beautiful swan in feathers.

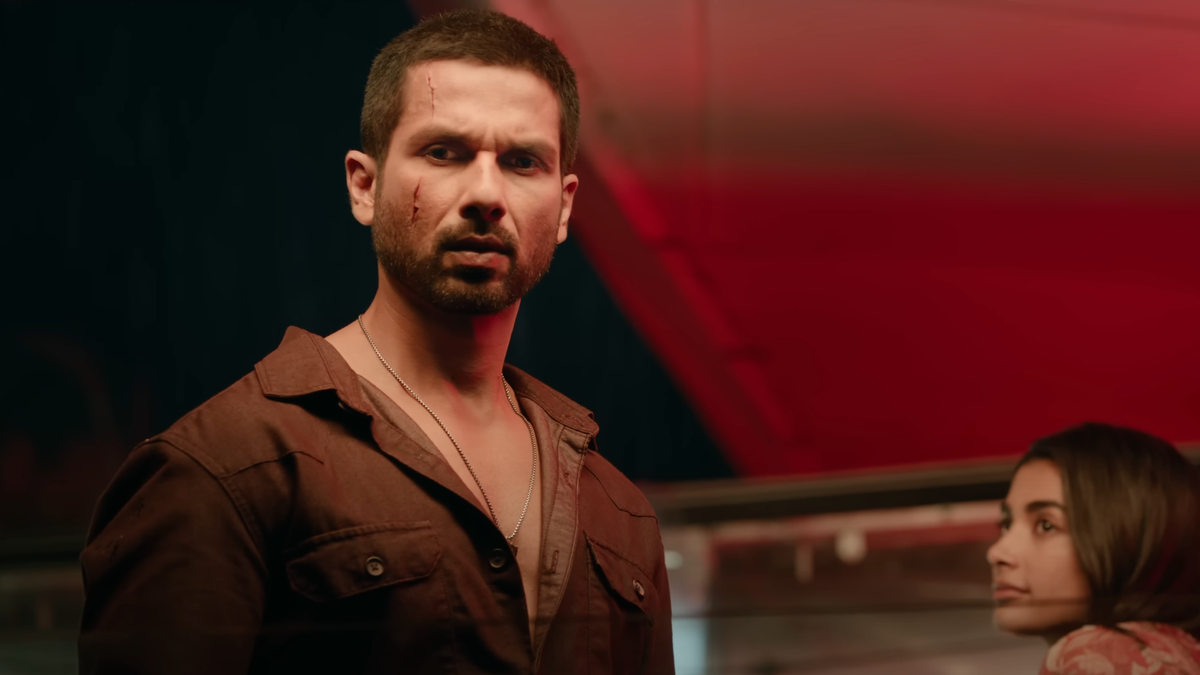

Here are five Un Certain Regard works that no one should miss, even if it means giving up a competition title: When the Light Breaks by Runar Runarsson from Iceland; Nora from Saudi director Tawfik Alzaidi; September Says by Franco-Greek actress turned director Ariane Labede; Konstantin Bozanov’s The Shameless, a poignant Indian drama; and the Indian police investigation story Santosh in which Shahana Goswami is the lead character.