A A fictional account of how the dairy movement took root in India, churn Social drama and commentary are brought together to deliberate on the difficult process of strengthening democracy. Almost five decades after it hit theatres, the title reflects the caste and class churn that continues to linger in our participatory democratic process, even as we enter the much-touted ‘amrit kaal’ of our independence from the colonial yoke.

A product of a time when parallel cinema was building bridges between art and commercial films, director Shyam Benegal refused to adorn his cinema with false expectations and sermons. He introduces an outsider into the harsh reality of rural life and through him depicts the spirit, ignorance and enterprise of the village folk.

Like the innovative idea of crowdfunding, Mr. Benegal proposes that social progress and profit can coexist on the same page. On the surface, it is inspired by the remarkable experiment of eminent dairy engineer and social entrepreneur Verghese Kurien, but a deeper look reveals the fractures of caste, class and corruption that still prevent India from becoming a great cooperative society.

Explanation

The film gives a chance to the idealism of the youth to flourish. At the beginning of the film when the hero Dr. Manohar Rao (Girish Karnad) reaches Sanganava village to form a dairy cooperative society, local businessman Ganga Prasad Mishra (Amrish Puri) who buys milk from the villagers for his private dairy comes in his way. Mishra is proud of building the village economy. Rao does not oppose his claim but says that now the time has come to move towards a more equitable system where arbitrariness of pricing and exploitation of caste and class hierarchy to satisfy an individual’s greed will end. This means reducing the role of middlemen who make the villagers dependent by giving them loans in their time of need and then fixing prices according to their interests. This deadly cycle of exploitation still exists, although in different forms, as we found during the farmers’ agitation. Trains passing through Punjab are getting delayed excessively because a section of farmers are still protesting.

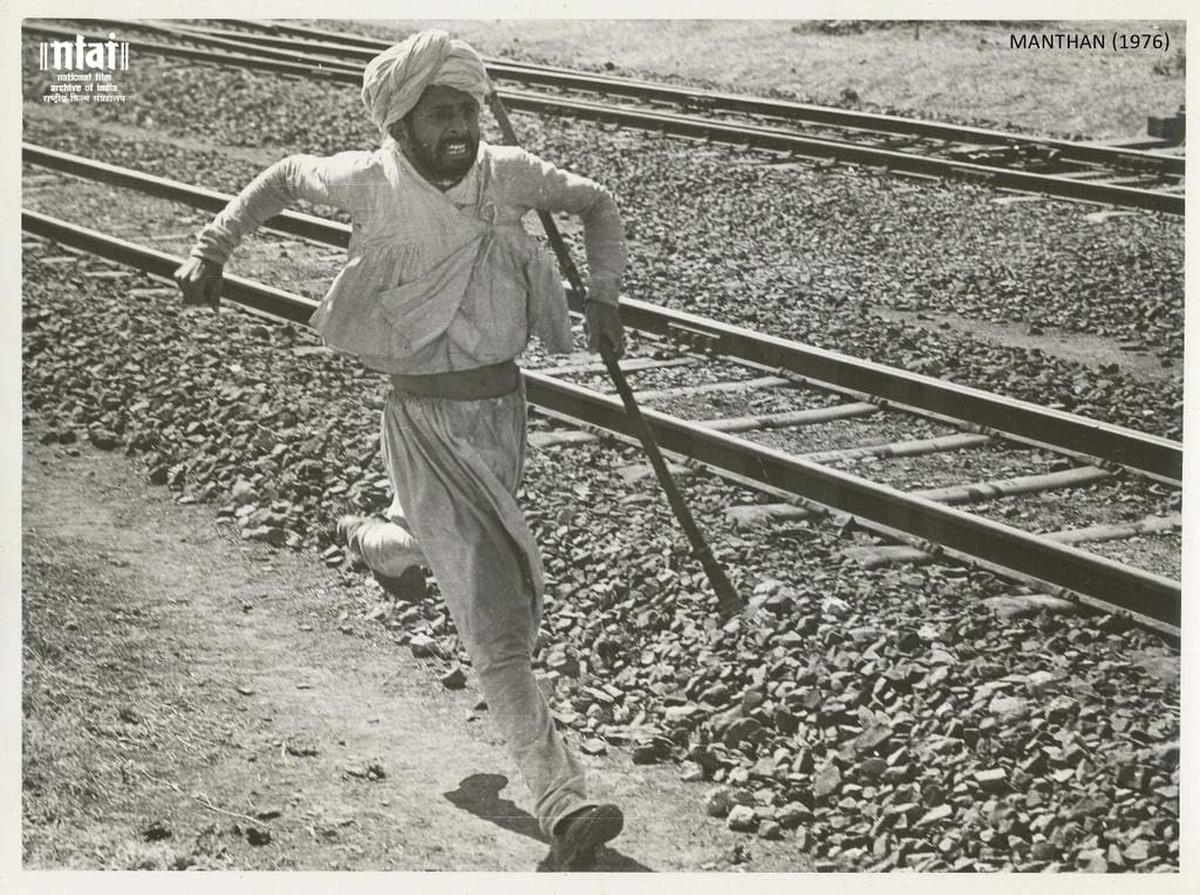

Smita Patil in a still from ‘Manthan’

churn The idea emerges because economic exploitation marked by systemic challenges is troubling the agricultural economy and collective action and advocacy for empowerment of the underprivileged is viewed with suspicion by the system as well as a section of the community.

Interestingly, when the locals arrive to receive the veterinarian dressed in suits who has just gotten off the train, the first sentence we hear is, “Sorry, the train has arrived on time”. Made during the Emergency, the film retains its independent voice and makes a scathing comment on the dark period for democracy when trains were said to have suddenly started running on time. The train scene turns into a harsh reality where the veterinarian, after getting off the train, refuses to board an overloaded horse-drawn carriage.

Entrepreneurship and caste

Vijay Tendulkar’s screenplay and Kaifi Azmi’s dialogues break down the class and caste structures that make it difficult for the democratic process to be implemented at the grassroots level. Rao’s insistence on equality threatens to disrupt the existing power structures in the village. A co-operative society is formed, but the arrogant sarpanch (Kulbhushan Kharbanda) still insists that the Dalits form a separate line while selling their milk. Rao’s educated wife Shanta also has casteist attitudes and shows little interest in her husband’s fight against injustice.

Kutcha roads, lack of basic healthcare facilities and gender discrimination are visible alongside the imbalanced development shown through Govind Nihalani’s long shots of fields and huts and the familiar rural sounds created by Vanraj Bhatia – all of which break the stereotypes of rural life. Preeti Sagar’s ‘Mero Gaam Katha Pare’ broke the stereotypes of rural life. churn This was the time when Hindi cinema turned to Western countries for inspiration.

The film is left-wing at heart, but it doesn’t let textbook idealism go empty-handed and keeps questioning the motives and attitudes of an urban outsider in a rural setting. Rao’s motives are scrutinised not just by the clever Mishra, whose milk business is expected to suffer because of the cooperative, but also by Rao’s good friend Deshmukh (Mohan Agashe), who isn’t as emotionally involved in the cause as Rao is.

Tendulkar has created an interesting contrast between the playful city boy played by Anant Nag and the committed urban boy played by Karnad, who is portrayed with his innate grace and balance in perhaps his most convincing and touching performance. Both have a soft corner for village girls, or one can say for the honour of the community, but their intentions are different.

Bindu, played by Smita Patil, is a complex character portrayed with irresistible conviction. She seems to yearn for freedom from the shackles of patriarchy but has not been able to develop the confidence and vocabulary to take the next step. Rao too is in a state of two minds. Mr. Benegal has beautifully portrayed the unsaid things between the two. Their silence and simplicity haunt us long after the credits roll and raise questions about the fundamentals of feminism and integrity.

Naseeruddin Shah’s Bhola represents an oppressed Dalit who has almost lost his voice due to feudal structures and is skeptical of the doctor’s concerns, until Rao shows him the possibility of equal opportunity through the power of the vote.

Naseeruddin Shah in ‘Manthan’

Finally, when Bhola addresses his community to ‘vote wisely’, this comes to mind.

The method-believing actor once told this reporter that he lived in a hut, learnt to make cow dung cakes and milked buffaloes. He would carry buckets of milk and feed the unit members to get into the character’s physicality right.

The power of crowdfunding

In an interview with this journalist in 2016, Mr Benegal had said, underlining that the common Indian has always supported good cinema, churn The funding source was much more organized and publicized, but it wasn’t the only time he used ordinary people’s money to get his story out to a larger audience.

In internal noise (1991), which was based on the Swadhyaya movement or self-reliance, the fishermen communities of Maharashtra collected funds and approached Mr. Benegal. Sussman (1987) the handloom cooperatives contributed to bringing alive Mr. Benegal’s vision of the plight of weavers. The tragic irony of the weavers was later reflected in the works of Prakash Raj as well. Kanchivaram (2007) is also included.

Before the Film Heritage Foundation came out with 4K technology, churn It was digitally restored in 2011 by Pixion and Cameo Restoration Sound, and that ‘restored version’ is available on YouTube.

However, poor print Sussman And internal noise Amul is waiting to get a new life.