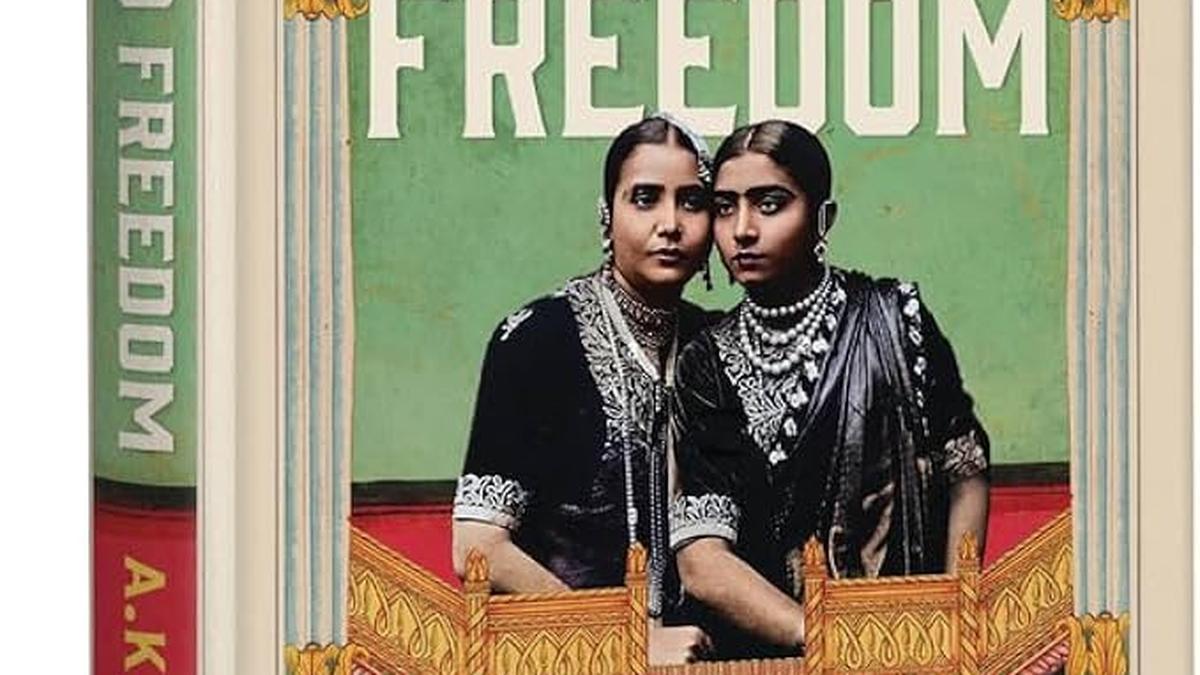

Historian AK Gandhi writes, “When it comes to giving credit to women in any profession or movement, we can see a marked indifference among historians.” The history of India’s freedom struggle has also been sorted out; The contributions of many people were ignored. In his book, dance for freedom, Gandhi pays tribute to one such lost community and their lost art: courtesans, forgotten heroines, and their journey “from luxury and influence to neglect and social contempt”. Tracing its roots to ancient Indian mythology and the early dynasties – Haryanka, Gupta – the performance art reached its peak in the medieval, Mughal years, and lost most of its strength in British India. It is this rise and fall that Gandhi embodies in his latest book.

Following the lives of five courtesans, Gandhi wrote a “soft history” of the status of tawaifs as educated, elite, respectable women before the arrival of Europeans; How his policies and decisions affected his position among the royals; And how the role of tawaifs in fighting the British was not recognised, reduced to nothing more than a footnote in Indian history. He interestingly separates the early British years into a period before and after the steamship. Steamships enabled British officers to bring their families to their respective stations, allowing European morality to reduce prostitutes to “mere prostitutes who also sang and danced”. As discrimination ended, several “anti-Nach” movements arose, led by the Brahmo Samaj, Arya Samaj, and revolutionaries, demanding its closure. brothel, Mahatma Gandhi also called the profession “a social disease” and a “moral leprosy” that must be eradicated.

Husna Bai

diplomatic skills

However, prostitutes had enough courage, grace, and spirit to use their art as a tool of activism. Born into the rich Lucknowi tradition of courtesans, Azizan Bai worked in Kanpur circles as a spy. Often seen on horseback, “in male attire decorated with medals, armed with pistols”, she continued to fight until her last breath. “Chaudharyyan of Banaras” Husna Bai encountered Mahatma Gandhi in a rally, organized a Kashi tawaif gathering and started singing patriotic songs. Begum Samru, widow of mercenary Walter Reinhard Sombre and ruler of Sardhana, was often called a sorceress or witch by her enemies for her wise practical ways. He took keen interest in learning administration and military techniques and displayed remarkable diplomatic skills. Begum Hazrat Mahal “turned from fairy to Begum” in the court of Prince Mirza Wajid Ali Shah of Awadh (Awadh). When the meek and timid prince, who had no inclination for anything other than poetry, failed to save his province, Begum Hazrat came forward to lead the protest and openly criticized the British, who “when He didn’t feel any shame when it came to not keeping it.” Dharman Bibi abandoned her newborn twins and sacrificed motherhood to fulfill her duty towards her husband, Kunwar Singh, and the nation. Today, when Kunwar Singh is immortal in history, there is less mention of the sacrifice of Dharman Bibi. People in Ara pretend not to know her, because she might embarrass their royal patron; “So his memory has been swept under the carpet.” Gauhar Jaan, who popularized Hindustani classical music, also gets an honorary mention in Gandhi’s book.

Gauhar dear.

History is unfair to them but courtesans live on in legends and folklore. Despite the insignificant place of tawaifs in history, there is no such shortage in popular discussion. Literature and cinema have done their due diligence: Kamal Amrohi Pakeezah (1972), Shyam Benegal Market (1983), Saba Dewan Documentary (2009)second song n or his book marriage certificate (2019), Amritlal Nagar This brothel owner (1959), by Munshi Premchand Seva Sadan (1919), by Vikram Seth a suitable boy (1993) and Manish Gaikwad’s recent memoir of his mother’s life in the decaying slums of Bombay, last prostitute (2023). Their struggles have been recognized by various art forms but their plight remains unheard.

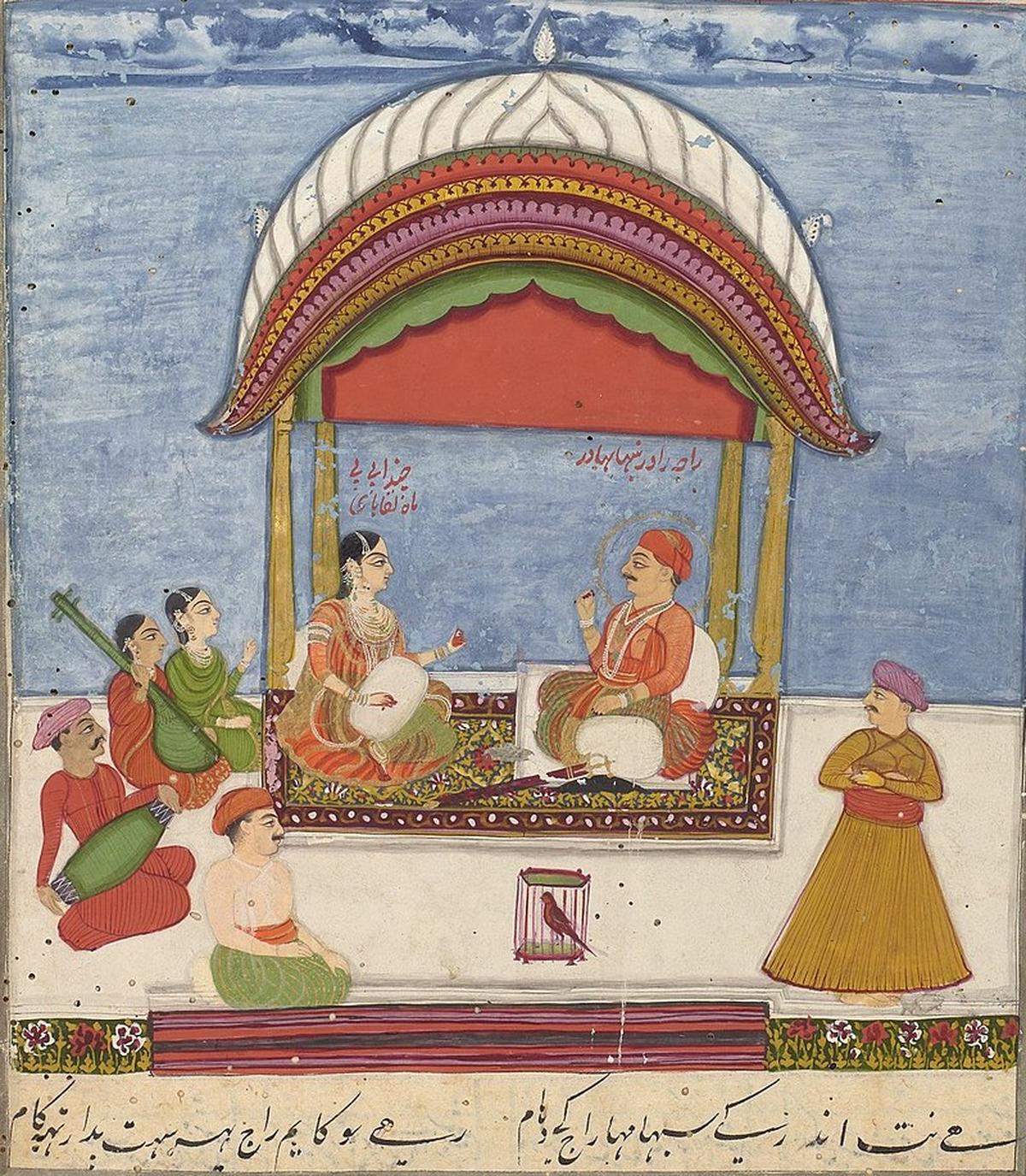

historical context

dance for freedomThe timely release makes an excellent companion piece to another cinematic tribute to tawaifs in pre-independence India: Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s OTT debut, Hiramandi, with its gorgeous, compelling setup and cruel, cunning and unforgivable characters, about which much has been written. The book provides the necessary historical context for traditions like Nath-utrayi that the web series portrays.

Popular ‘Sakal Ban’ song of Hiramandi

After World War II and at the height of the Quit India Movement, HiramandiIts inhabitants and its visitors stand at the pinnacle of the violent, immoral ways of the British and their duty to their own people. Hiramandi Presents tawaifs as a community and not as individuals who broke gender barriers to emerge as revolutionaries.

The five courtesans of AK Gandhi’s book are much more fortunate than the courtesans of Bhansali’s world, where relationships are delicate. Love did not triumph in the show, although it was glorified and much sought after. The patrons are not as loyal as real-life Wajid Ali Shah and Kunwar Singh, and the courtesans are not untouched by jealousy, greed or opioids. The Nawabs have very few powers, except a few that are borrowed from their British masters, unlike the Nawabs described in the book, who are comrades and talented poets, if not brave fighters.

From Hiramandi

When seen in the light of AK Gandhi’s book, the web-series shows the courtesans possessing a richness that they had lost up to that point in history. This is commonly known (and reinforced by). dance for freedom) that as punishment for the prostitutes’ rebellion in the 1850s, the British confiscated their properties, relocated them and imposed heavy fines. They imposed strict, discriminatory laws (on marriage, adoption, etc.), which left courtesans powerless. This retaliation was followed by a boycott of the Kothas by the Nawabs, causing the courtiers to lose their wealth and social standing. The show objectifies and sexualizes them in the same misleading way that the British did; Some A.K. Nearly 300 pages are spent in refuting Gandhi’s book.

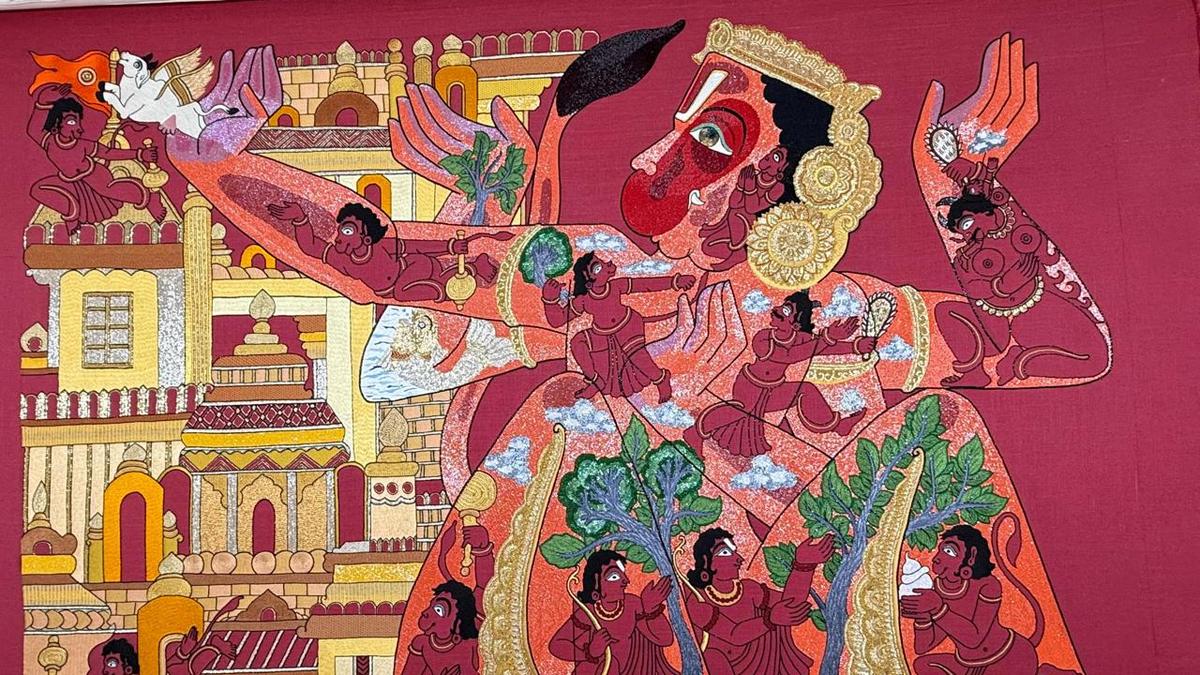

Courtesans excelled in music, dance, theater and literature. Mah Laka Bai is shown singing in the picture.

HiramandiAlthough set several decades ahead of the book, it seems to offer only a glimpse of his role in history. The introduction of courtesans into the freedom struggle and a new purpose in nationalism is a consequence in Bhansali’s show, not a source of the story.

The closing lines of the show rightly state, “A woman’s struggle never ends.” Historians like AK Gandhi and filmmakers like Bhansali revitalize historical debates, and facilitate new ways of looking at history and history-makers.

Nandini Bhatia is a freelance feature writer.