Katherine Scofield’s latest book is an invaluable contribution to the few books written on Indian music. This book is not only a testament to his erudition and thorough research into a subject that many people don’t know about, but it is also an interesting page turner. His thought-provoking compositions bring alive the world of music of that era.

Limiting herself to the period between 1748 and 1848, “one of the most important periods of change for Hindustani music”, Katherine regrets that the period “has not been properly mapped”. Due to, “a widespread belief” that the composers were illiterate. During this period the 2000 year old tradition of writing music scriptures came to a halt and music connoisseurs came to be considered ignorant and uneducated. However this assumption has been proven wrong by modern researchers, and the book relies on writings on music during this period; Which are “lying in the archives”.

The six essays, dealing with different topics and spanning different time zones and regions, have been skillfully combined. In 1752, Inayat Khan Rasikh wrote the first biographical collection (tazkira) on musicians. Rasikh compiled a record of composers from the reign of Akbar to Aurangzeb, “the Mughal Empire and the golden age of Hindustani music”.

The longest entry in this work relates to an anecdote from the life of Khushal Khan ‘Gunasamudra’ (d. 1675), great-grandson of Mian Tansen. His father Lal Khan was so talented that when Tansen heard him singing, he sent his son Bilas Khan to train under him, and later made Lal Khan a part of his family by marrying Bilas Khan’s daughter. .

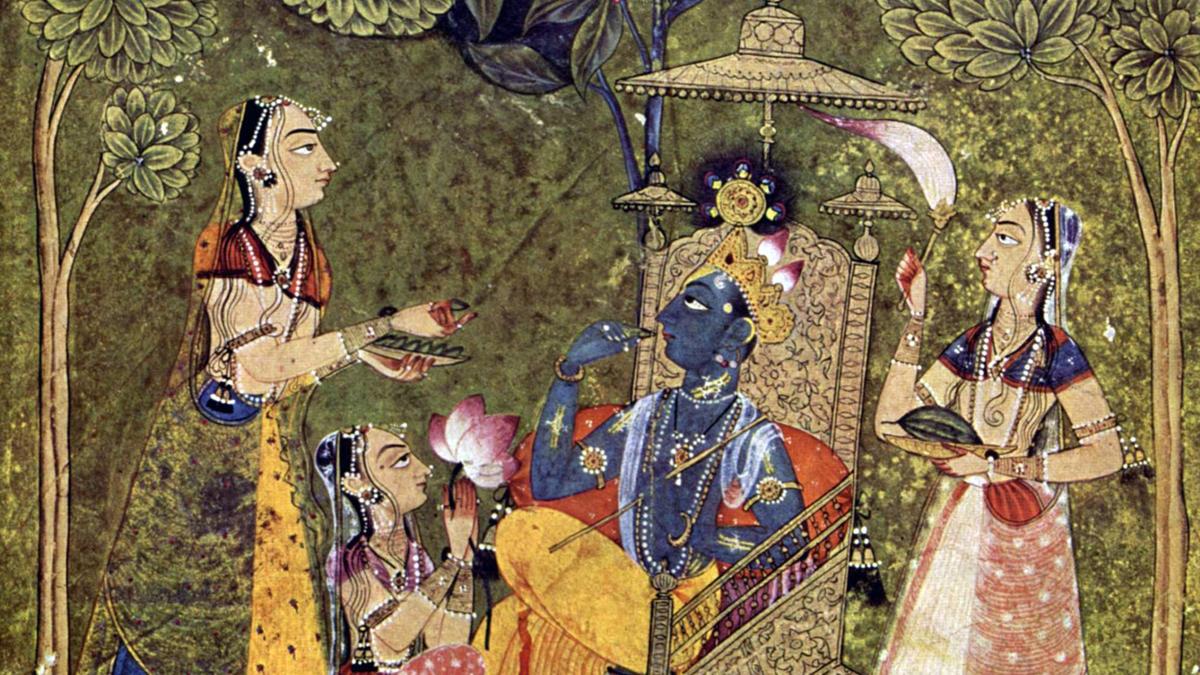

A singer or artist. , Photo Credit: British Library

Interestingly, 400 years ago, talent was recognized and musical training was not limited to the family. Lal Khan became the chief musician in the court of Shah Jahan, a title later passed on to his talented son Khushal.

At that time musicians used to sing while standing; Rasikh writes about young Khushal and his brother Bisram standing on the edge of the carpet below the Emperor’s throne and playing ‘tambur’ and lending their voice to their father Lal Khan. The carpet is mentioned by a later maestro, Sadarang (one of the greatest singers of his time), as “Only he who does not set even one foot outside the carpet will earn the royal title of high glory.”

After attracting the King’s attention with his wonderful rendition of Raga Todi, Khushal Khan came out of the carpet and started speaking symbolically. Seeing the emperor completely mesmerized by the music, Khushal signaled to an officer to get him to sign a petition, which Shah Jahan unknowingly did, but later realized that he had been duped. After this he threw the singer out of the court.

Apart from such interesting anecdotes, this book also provides a lot of information. Apparently, there were four communities that participated in musical gatherings (Majlis) – the Kalavantas who performed the Dhrupad and played the ‘Bin’ (Rudra Veena) and the Rabab, Qawwal, the instrumental accompanists of the Qawwals and finally, the prostitutes.

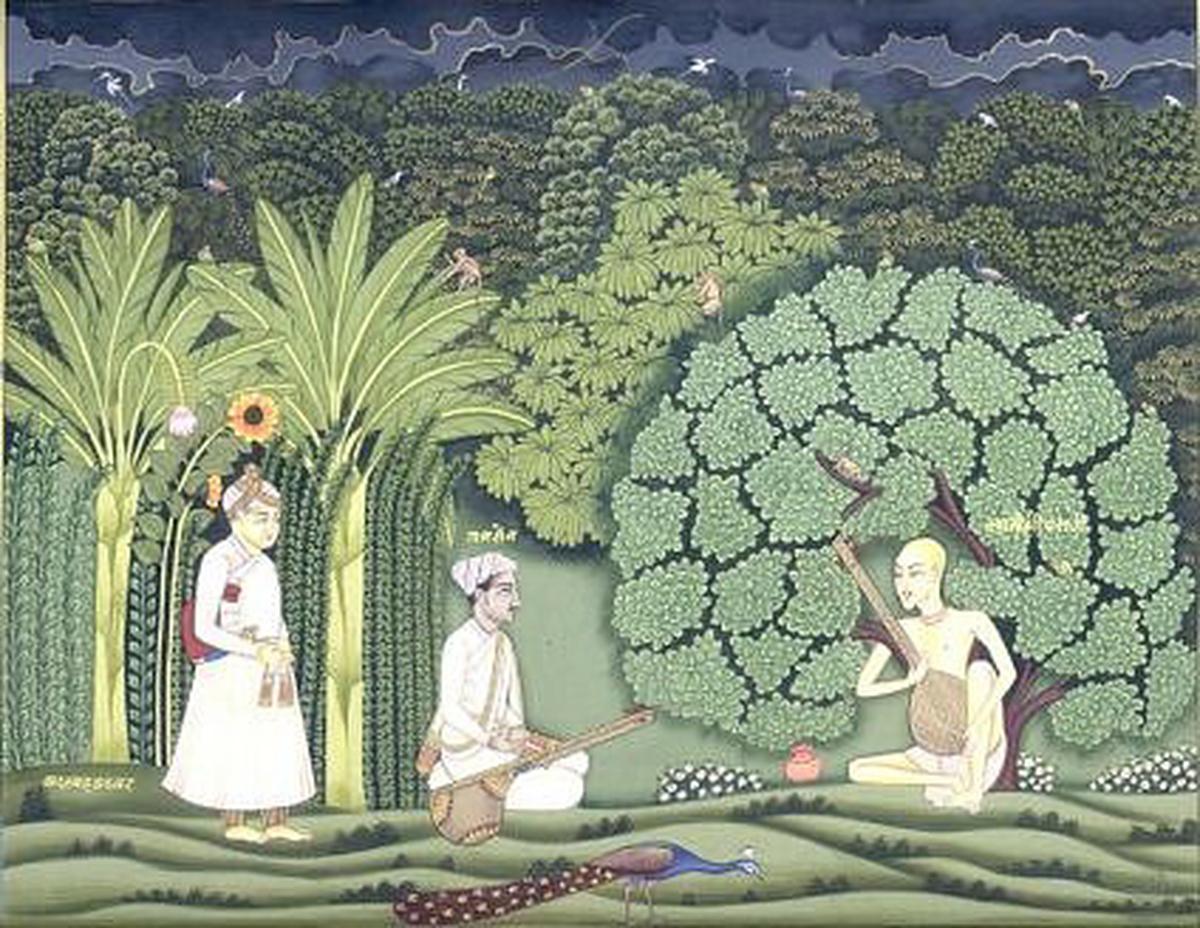

Tansen and Akbar went to Vrindavan to meet Swami Haridas. , Photo Credit: Courtesy: National Museum, Delhi

The list of great musicians from the pre-Tansen period to the 1800s takes us to now forgotten musicians like Nayak Baiju (who, contrary to popular belief, predated Tansen), Nayak Gopal, Amir Khusro, Nayak Bakshu, Tansen, Lal Helps in knowing. Khan, Baz Bahadur and Roopmati, and Niamat Khan Sadarang and their descendants.

Sadarang or Mian Niyamat Khan, the famous Benekar (today he is better remembered for his Khayal), is said to have fallen from royal grace and had to leave the court. His cousin, the courtesan Lal Kanwar, married Jahandar Shah, a grandson of Aurangzeb, and apparently Sadarang was also promoted to a high post. But when Jahandar Shah was strangled to death by his own courtier, Sadarang went on to appear again during the time of Emperor Muhammad Shah. Because of his amazing imagination, he is mistakenly credited with creating the look, which was actually popular in royal courts from the 1660s onwards.

The rivalry between Sadarang’s nephew and son-in-law Adarang and Tansen’s descendant Anja Baras Muhammad Shahi has been discussed. This book is not limited to the music of the Mughal court. In 1788, at the Awadh court of Asaf ud Daulah, Catherine writes of a musical conversation between the Kashmiri prostitute Khanum Jaan and Sophia Elizabeth Plowden, the wife of an East India Company official. These were later compiled as “Hindustani Airs”, which were popularly performed in the 1850s.

Going to Hyderabad, Catherine writes about Anup Raga Ragini Roz O Shab, was written around 1833, and is currently housed in the Salar Jung Museum, Hyderabad. The list of ragas “can tell different stories – it could easily fill a book in itself.”

Katherine highlights how sources for musical authorship can be contradictory – Colonel Skinner’s notes on ‘Kalavants’ differ completely from other sources, making cross-checking necessary. His book is a compilation of vast research that took more than five years. “I used mostly Persian and to some extent Urdu, Brajbhasha and Hindi texts.”

Today Catherine’s views on the ‘thaat’ system are more relevant – “It is well documented that modern composers do not use shared scales to conceptualize raga relationships…Ghulam Raza’s system (a treatise in 1790–93 Propounded in ) pays more attention to modern raga relationships than Bhatkhande”.

The most poignant chapter is about Andhe Mian Himmat Khan, ‘Keeper of the Flame’, who belonged to the lineage of Sadarang, who died early during the reign of Bahadur Shah Zafar (1837–58). He tried to preserve his knowledge through scriptures asal al-usul, Since he had no son, he took his daughter’s son, Mir Nasir Ahmed, as his last ‘Bin’ disciple. Mir Nasir Ahmed had to flee Delhi after 1858, and live under the protection of the Kapurthala prince, Bikram Singh (incorrectly mentioned as Bikramjit Singh in the texts).

Katherine’s research brings to light an unknown part of our musical history, lost to time. In his words, “The genealogy important to 20th-century composers is not the same as those considered central by Mughal patrons and composers in their own time.” She concludes, “There are so many untold stories in this book. That’s because I don’t have the lifetimes I would need to tell them all.”