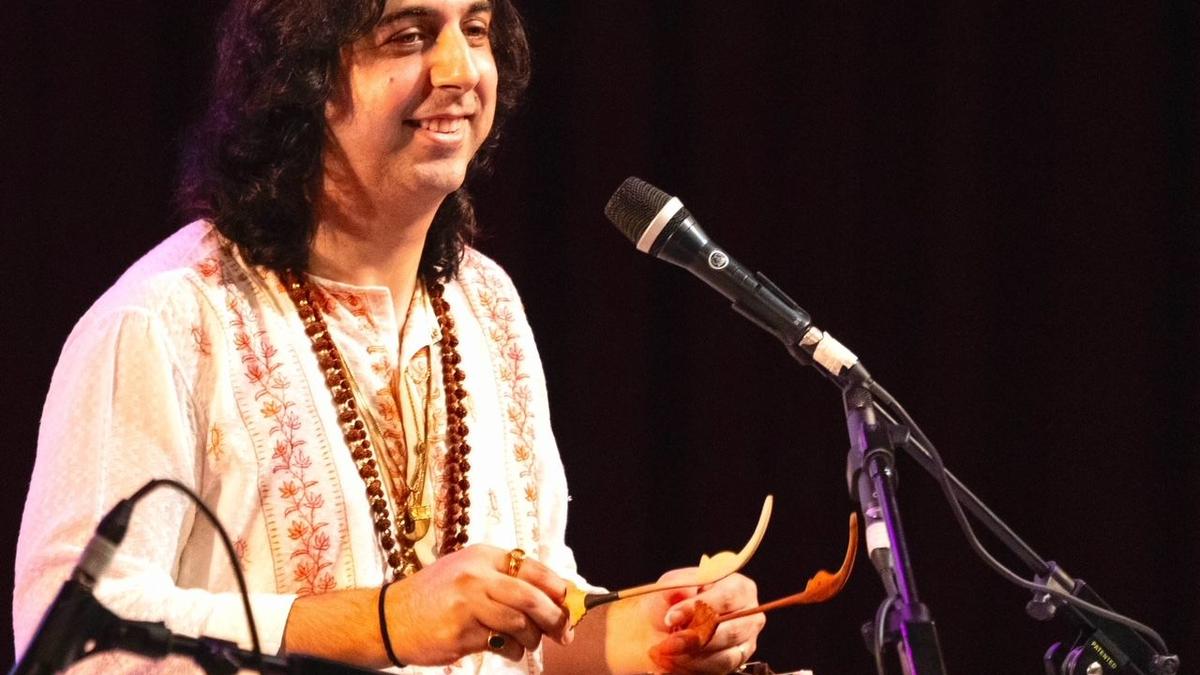

Abhay Rustam Sopori. , Photo Courtesy: The Hindu Archives

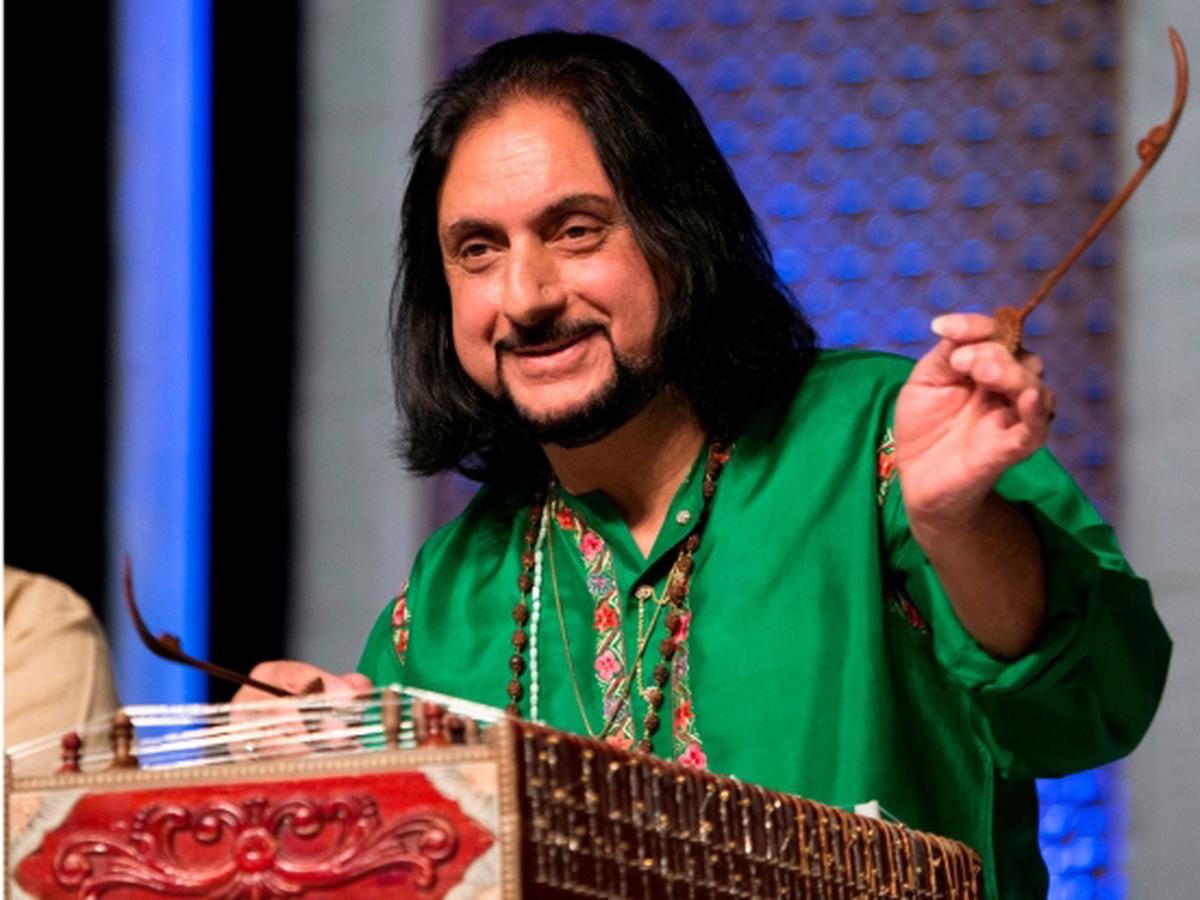

Watching Abhay Rustam Sopori play his composition Raga Bhagwati on Santoor at a concert during the Pandit Kshitpal Malik Music Festival in Delhi recently, one was reminded of the long journey of this instrument from the hills to the plains. Thanks to the efforts of two musicians from Jammu and Kashmir – Pt. Shiv Kumar Sharma and Pt. Bhajan Sopori, Santoor gave up their ‘folk’ tag to become a part of the world of classical music. Both exponents brought the necessary changes to enable the 100 strings of the Santoor to reproduce the raga, tala and swara.

Abhay’s santoor has also been modified. Its deep frets make it sound like a flute, while the bow-like movement of its strings is reminiscent of a violin. Although traditionalists may view this as tampering with its distinctive sound, it enhances the listening experience.

Apart from Bhagwati, Abhay has four more ragas in his account. All of them have a specific shape (form). For a new raga to be recognized, the creator must be able to interpret it easily, and its grammar must be clearly visible. A key phrase in Bhagwati is ‘Pa Dha Ni Sa’.

Pt. Bhajan Sopori brought the necessary changes to enable the Santoor to reproduce the raga, tala and swara. , Photo Courtesy: The Hindu Archives

His father Bhajan Sopori, who belonged to the Sufiana gharana of Santoor, also composed ragas. Abhay seems to have imbibed his father’s composition skills.

At the concert, after a brief aalaap, Abhay played the Jor Khand with Rishi Shankar Upadhyay on the Pakhawaj. The style of playing was not the traditional ‘tar paran’ pakhawaj accompaniment, involving similar complex stroke work on both instruments, instead the performers got into a creative mode and moved to the rhythm together in a spectacular culmination. After this, Mithilesh Jha provided accompaniment on the tabla in a rhythm composition. Abhay’s ‘Barahath’ follows a system, he is not just building on a tune.

During a conversation after the concert, Abhay revealed that his father had instilled in him the importance of this systematic approach. They were asked to analyze what they played, how they played and why they played.

Talking about his family’s association with the instrument, Abhay revealed that his grandfather had increased the number of bridges on the santoor from 25 to 28 in the 1930s. This was done to add more strings to play more notes. Abhay’s father further improved its sound by adding some more bridges and strings. Abhay, during his experiments with the instrument, introduced flat ‘jawari’ bridges. His Santoor, made by the Goddess of Banaras, has 43 bridges and one can play three octaves on it. With ‘means’, notes can be played up to five and a half octaves. Although there are 100 strings, Abhay’s modified santoor has additional ‘chikari’ and ‘tarab’ strings while the ‘tumba’ helps balance the instrument and acts as a resonator.

According to Abhay, these amendments are not planned. “They happen naturally because you’re constantly engaged with music.”

Abhay also uses wider mallets (Kalam) with greater sound support and volume control. Striking technique involves four movements – finger, wrist, elbow and shoulder, which provide depth and variety to the quality of tone.

With increased scope and range, Abhay Sopori wants to take the santoor to new musical settings.

published – October 18, 2024 02:57 PM IST