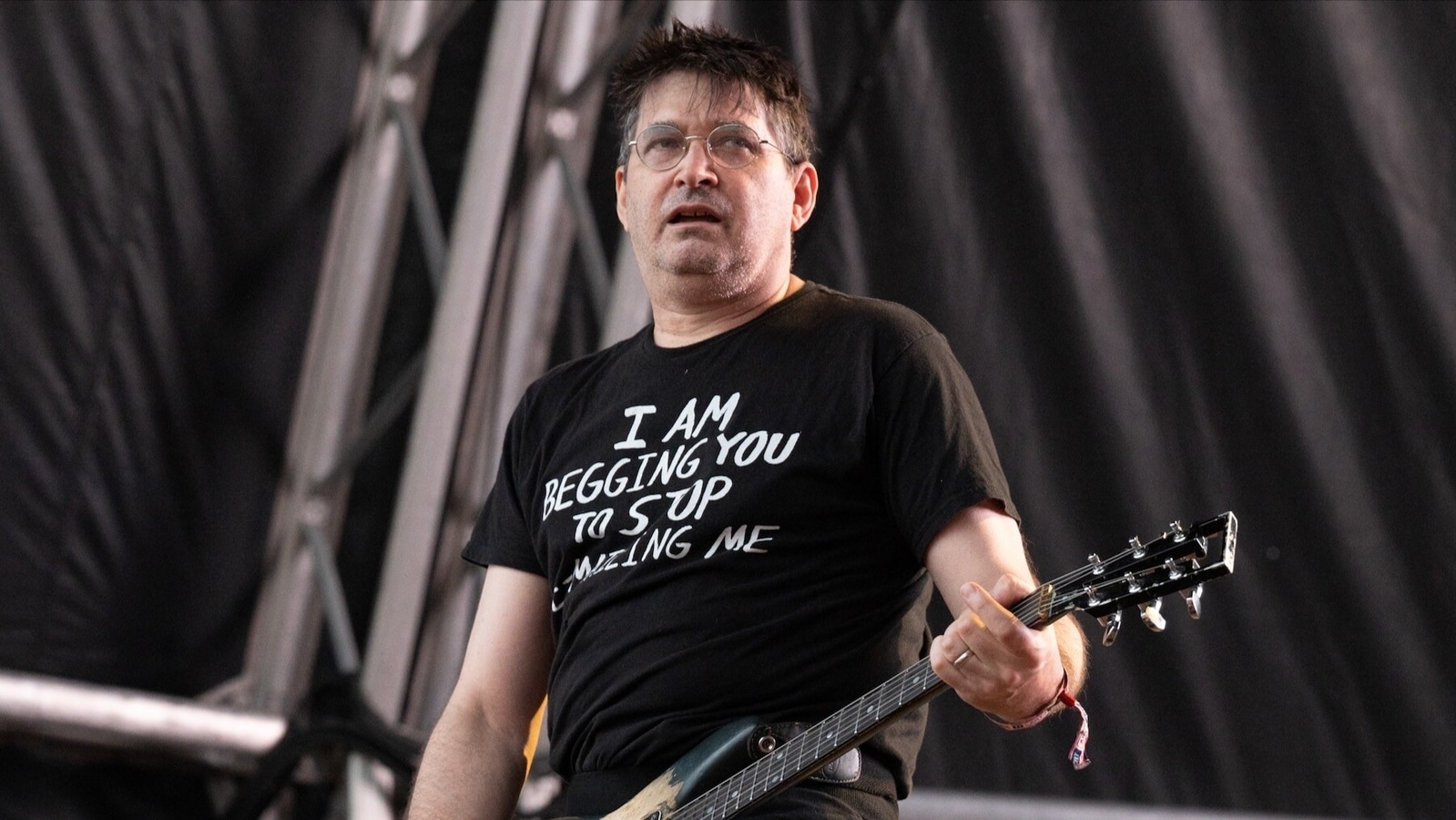

Alternative rock pioneer and renowned producer Steve Albini, who shaped the musical landscape through his work with Nirvana, the Pixies, PJ Harvey and others, has died. He was 61 years old.

Brian Fox, an engineer at Albini’s studio, Electrical Audio Recording, said Wednesday that Albini died of a heart attack Tuesday night.

In addition to his work on canonized rock albums such as Nirvana’s “In Utero”, the Pixies’ breakthrough “Surfer Rosa” and PJ Harvey’s “Rid of Me”, Albini was the frontman of the underground bands Big Black and Shellac.

He rejected the term “producer”, refused to take royalties from the albums he worked on, and requested that he be credited with “Recorded by Steve Albini”, a well-known label, on those albums. On which he has worked.

At the time of his death, Albini’s band Shellac was preparing to tour their first new album in a decade, “Two All Trains”, which would be released the following week.

Other acts whose music was shaped by Albini include Joanna Newsom’s indie-folk opus, “YS” and releases from bands such as The Breeders, The Jesus Lizard, Hum, Superchunk, Low and Mogwai.

Albini was born in California, grew up in Montana, and fell in love with the do-it-yourself punk music scene in Chicago while studying journalism at Northwestern University.

As a teen, he played in punk bands, and in college, the presenter wrote about music for the indie zine “Forced Exposure.” While attending Northwestern in the early ’80s, he founded the abrasive, noisy post-punk band Big Black, known for their fiery riffs, violent and taboo lyrics, and their use of a drum machine in lieu of a live drummer. goes. It was a controversial invention at the time, from a man whose career would be defined by risky choices. The band’s most famous song, the ugly, explosive, six-minute “Kerosene” from their cult favorite album, 1986’s “Atomizer” is the perfect proof – and not for the faint of heart.

Then came the short-lived band Rapeman – one of Albini’s two groups that inevitably came out with offensive names and obscene song titles. In the early ’90s, he formed a brutal, distorted noise-rock band called Shellac – which evolved from Big Black, but was still punctuated by guitar tones and aggressive vocals.

In 1997, Albini opened his renowned studio, Electrical Audio, in Chicago.

“The recording part is the part that matters to me – that I’m creating a document that records a piece of our culture, the life’s work of the musicians who are hiring me,” Albini told The Guardian last year. When he was asked about some of the famous and much-loved albums he has recorded. “I take that part very seriously. I want the music to live on for all of us.”

Albini was a larger-than-life character in the independent rock music scene, known for his visionary productions, unapologetic irreverence, sharp sense of humor, and criticism of the exploitative practices of the music industry – as evidenced by his landmark 1993 essay “The Problem ” is detailed in. With the music” – as much as his talent.

In later life, he became a notable poker player and was apologetic for his past indiscretions.

“Oh man, a heartbreaking loss of a legend. Love to his family and countless colleagues,” wrote actor Elijah Wooden

Author Michael Azerrad, who included a chapter on Big Black in his comprehensive history, “Our Band Could Be Your Life: Scenes from the American Indie Underground, 1981–1991,” also posted on X. “I don’t know what to say about Steve Albini’s passing,” Azerrad wrote. “He had a brilliant mind, was a great artist and had the most remarkable and inspiring personal transformation. I can’t believe it.” That he is gone.”

Albini is survived by his wife, Heather Whinna, a film producer.